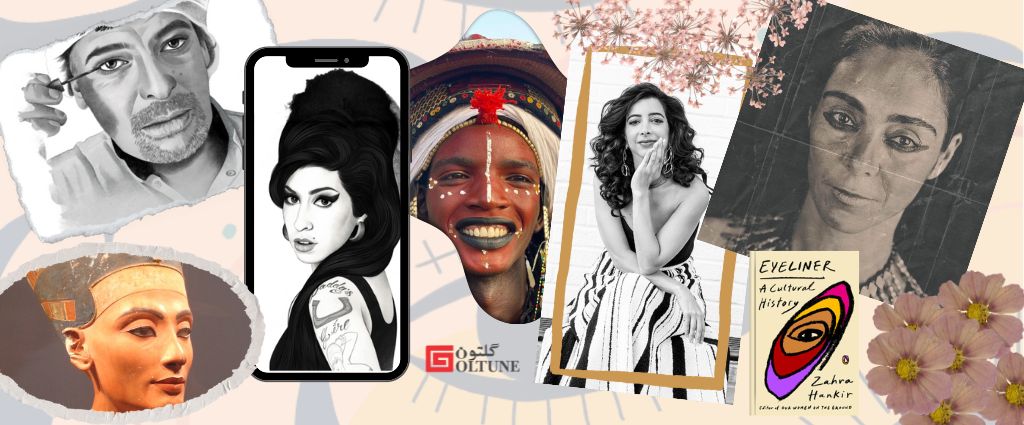

From the distant past to the present, with fingers and felt-tipped pens, metallic powders and gel pots, humans have been drawn to lining their eyes. The aesthetic trademark of figures ranging from Nefertiti to Amy Winehouse, eyeliner is one of our most enduring cosmetic tools; ancient royals and Gen Z beauty influencers alike would attest to its uniquely transformative power. It is undeniably fun—yet it is also far from frivolous.

Zahra Hankir joined Sara Jamshidi for a conversation about eyeliner and its significant status.

Please read the transcript of the selected parts of our conversation.

You provide a great deal of information in Eyeliner, A Cultural History. How did you organize the information?

The book is very travel-oriented. I traveled to six different locations for this book.

It’s 10 chapters. Each chapter is quite distinct in terms of sort of the areas of coverage.

So the first section focuses on the origins of eyeliner. So you start with ancient Egypt and therefore I wanted to remain in the African region. The second chapter then takes you to Chad where you learn about the Wadaabi tribe.

Women judged the men for their beauty in the African Wodaabe tribe.

And then I wanted to keep on transitioning regionally, right? So I then went into the Middle East and then the Arab world. Then we have Iran and Jordan. And then we have a section on Asia where we have Japan and India. And then towards the end, we get a little bit more focus on the West.

We do have a chapter on the Mexican American Chola community in California. So there’s a little bit of Latin America in there, but we’re getting closer to the West.

Then we have Amy Winehouse and Drag Queens and then we have Influencers. So I was really thinking regionally and also historically with the way that I was arranging the book chapters.

Why do you love Amy Winehouse so much?

Yeah. I mean, Amy Winehouse is such an important figure when it comes to the iconic looks of eyeliner.

For me, she’s actually on par with Nefertiti. I can’t think of many figures who have such a distinct eyeliner look, it traveled all the way to the edges of her eyebrows. Sometimes it kind of went up to her temple. It’s beyond the aesthetic.

It wasn’t just about what she looked like. It was about how her eyeliner played a significant role in her transformation as a celebrity, as somebody who we became very familiar with, but who was also hounded by the press in a very negative way for the way that she was living her life.

And as we know, she died very young. She was only 27. The way that the press criticized her had to do a lot with her aesthetic and her eyeliner.

So, you know, people would say it [her eyeliner] was asymmetrical. It was smudged. It was smeared. And what I write in the book is that the absence of her eyeliner actually said a lot more than the presence of it as well. She was a fascinating character to study.

Why did you become interested in eyeliner?

I think it’s a very fair question, especially because my first book was quite serious.

[In my books] I try to de-center Western narratives and to really uplift and celebrate the contributions of communities of color. So the first book was the contribution to the journalism industry. And the second one is about the contributions to the beauty industry.My personal fascination with eyeliner started with observing my mother apply eyeliner when she was living in the West. When we were living in the UK during the Lebanese Civil War, she had a lot to deal with. I mean, she was missing her family.

She was concerned about her family, but she also had six kids. She also had to raise us. My dad was away very, very busy with work most of the time. Every morning she would have a moment of silence, of self-care, where she would apply her eyeliner.

It is known as coal in my region and ‘sormeh’ in Iran.

I realized, even as a young girl, that it was much more than about beauty. It was about her heritage. She connected to something back home. In the same way that music might connect her, or food might connect her. It was an object, a tangible object that made her look a certain way, or feel a certain way. So that was my initial interest, obsession, and love with eyeliner.

It really came through my mother and then it developed over the years.

What is the characteristic of a good eyeliner in your opinion?

Great question.

Eyeliner is so personal. It depends on the person and the message the person is trying to convey. It can also depend on the shape of the eye. It can also depend on, what culture or community you belong to. The role that eyeliner plays physically is to enhance the eye.

So it is to make the eye look a particular shape depending on whichever shape you’re going for or perhaps you want to make the eye look bigger. Sometimes you might want to make it look smaller. Again, beauty standards vary from culture to culture.

So for me, eyeliner connects me to my Arab heritage, my Egyptian Lebanese heritage, but also I’m telling the world the aesthetic I want to convey.

It’s about something far deeper.

Please let me tell you a story. My grandma used to make her own ‘sormeh’ or eyeliner. She had a tiny small leather pouch. Whenever she wanted to make ‘sormeh,’ she would mix coal powder with almond butter, which she made herslf and Vaseline. I watched her with fascination every time she made her ‘sormeh.’ “This is for medicinal effect,” she would tell me. In your book, you mention the medicinal effect of eyeliner. Can you talk about that?

Yeah.

Well, first I want to comment on how beautiful the anecdote is of your grandmother. I want to say that the story of eyeliner is also the story about mothers and daughters and grandmothers and granddaughters and all of these beautiful cultural traditions that can be quite ritualistic.

And the pouches themselves are oftentimes beautiful; also the containers and the applicators. So thank you for bringing that up.

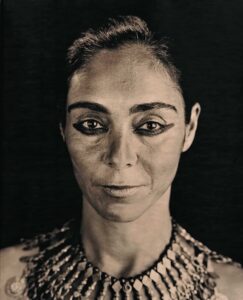

Eyeliner originated in ancient Egypt where it was known as coal or kohl and it was made from natural materials and those natural materials were malachite and galena, or similar sort of minerals.

It could also be plants or a tree sap or anything that could be burned and could create a powder. And if you had like your grandmother did, you would also need a liquid to help make eyeliner paste, right?

The liquid could be saliva, rose water, or any number of materials.

So that context is important because we wouldn’t know what the medicinal properties [of eyeliner] are unless we know what the ingredients are.

There have been scientific studies that show that some formulations of coal can provoke an immune response in the eye and that can then treat a bacterial infection, for example.

I’m very careful when I discuss this because the immune response can be triggered from very small concentrations of lead, which was actually used in ancient Egypt, but lead is very toxic as we know. So it’s very dangerous to use lead anywhere near the eye. So, therefore, modern formulations of coal that may contain lead tend to contain very high levels of lead that are extremely toxic to the eye.

What I will say is that there have been scientific studies that show that the tiny concentration of lead that was used in ancient Egypt did provoke an immune response.

So that’s not to say that people should use that today because coal containing lead, especially in the global south, is a huge cause for concern.

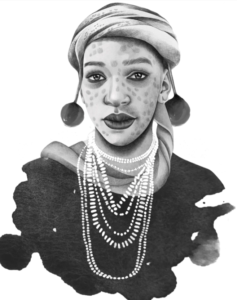

I think in chapter two, you write about the Wodaabe tribe and men’s beauty contest that’s been judged by women. Tell me more.

So I traveled to Chad for that chapter. The Wodaabe is an ethnic group, a nomadic group that is a subset of the Fulani group.

So I traveled to Chad for that chapter. The Wodaabe is an ethnic group, a nomadic group that is a subset of the Fulani group.

And for them, beauty is a part of their moral code. It is very important to them.

Therefore, the men will wake up at the break of dawn. So this beauty contest happens every year in different locations and usually it attracts two clans [for competition].

So two clans will be competing and it attracts members of surrounding areas to witness it. But it is the women who are judging the men for their beauty.

As a young girl, I realized that eyeliner was much more than about beauty for my mom. It was a tangible object that made her look a certain way, or feel a certain way.

Part of the idea or concept of beauty there is the idea of contrasts. So the whiteness of the eye against the darkness of the framing of the eye. So that would be the coal and then the whiteness of the teeth against the darkness of the lips. They often blacken the lips. The men spend hours really trying to maintain this very beautiful appearance that they have during this beauty contest.

They dance during the beauty contest. They have a very sophisticated dance. They dance like the bird the heron. They move like the bird the heron. They move their eyes around. They chatter their teeth. It’s a very, very fascinating experience to observe.

The coal is so important to the men that they wear it on necklaces in pots as a talisman, or next to a talisman. So you see there that it’s not just about how it makes them look.

It’s a lot deeper than that. And it also plays that role, the medicinal role, and it also guards against the glare of the sun. So it has multiple purposes there.

I love when you said women judged men for their aesthetic.

So refreshing.

Yeah, very refreshing.

What didn’t you include in the book?

Yeah.

You know what? At one point I actually made the joke, like, the better question is who doesn’t wear eyeliner and why don’t they wear it?

You know, that could have been a whole book, you know, because it’s ubiquitous everywhere. It’s in so many different countries, cities, communities, rural communities all around the world.

A signature question of our show is to ask our peaceful bridge makers to share memories, anecdotes, or stories about peace, kindness, and compassion. What’s your story? Or what does peace look like to you?

This is a really good question, especially at this moment of time what’s happening in Palestine.

I struggled a lot with talking about this book and having it published while the war was unfolding.

I struggled a lot with talking about this book and having it published while the war was unfolding.

And I spoke to my mother about it and she, my mother’s always right, but she said to me at one point to be kind and compassionate to myself and to recognize that amidst all of the stories of suffering and pain, it’s also important to document stories of celebration when it comes to our own culture and preserving our cultural heritage. So that helped me reframe the guilt that I was feeling when I was talking about something like eyeliner when the world felt like it was on fire.

It was this idea of we also still need to be uplifting these stories that celebrate our contributions to culture. So that is a thought that I have.

Very good, very well put. Thank you so much Zahra.

Please Pledge to Our Independent Peace Journalism.

Goltune is editorially independent. We set our agenda. No one edits our editors. No one steers our opinion. This is important as it enables us to stay true to our values.

Every contribution we receive from readers like you, big or small, goes directly into funding our journalism. Please support Goltune, large or small.

Send your contributions to our PayPal account: [email protected]

Or, Click the link to pledge your support.

Thank you,

Goltune Editorial Team